Samantha Hobson —

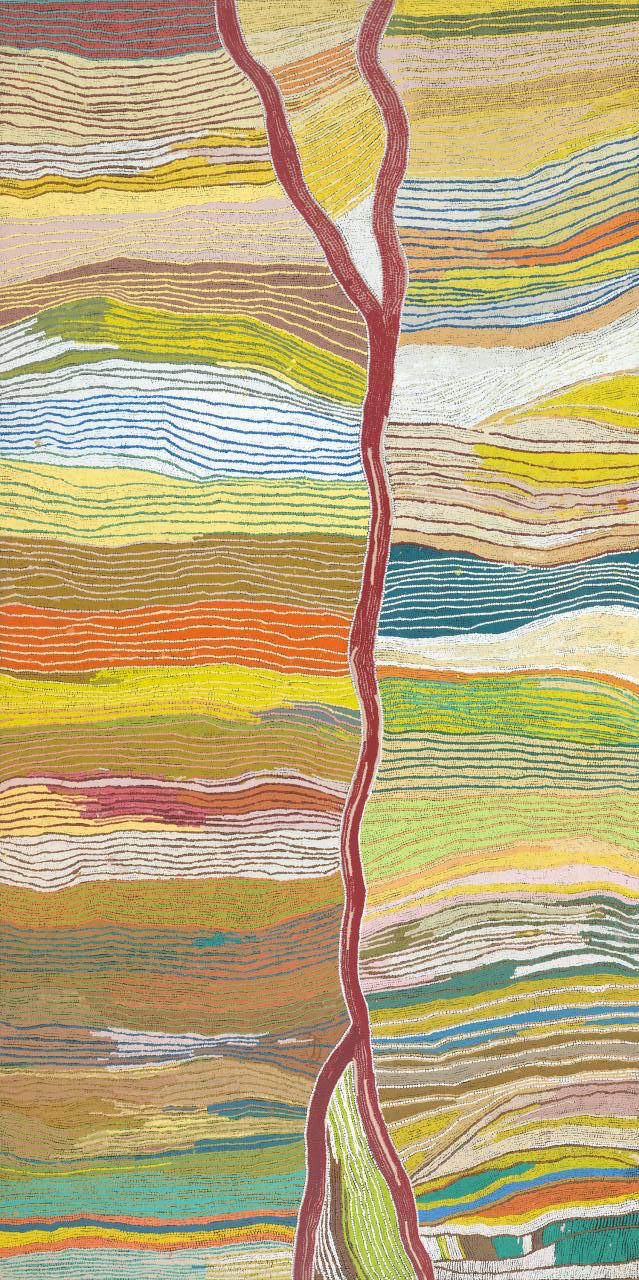

On entering the latest exhibition — Who’s afraid of color at The National Gallery of Victoria — you are surrounded by many beautiful forms of indigenous culture and art. Many indigenous artworks are concerned ritual and myth and maintain a direct link to traditional processes. These processes are part of the tribal consciousness and identity, an expression of communal culture, something fundamental in most indigenous art.

I was particularly fascinated by one artwork that glistened in a dark room. An expressive, vibrant painting with splashes of blood red and deep blue, harmoniously collaborating to express — or warn — of ribald passion and immediacy. If art could be considered a reflection of the self and one’s surroundings, I began to wonder at the environment which encapsulated this work. It was reminiscent of the work of abstract expressionists Jackson Pollock whose paint splashed and dripped across the whole canvas creating sensations of fluidity and unease.

This piece titled Bust ‘im up, by artist Samantha Hobson, seemed out of place with its contemporary narrative and lack of inherent iconography. Instead of an earthy, western desert palette of ochres painted on bark, we are presented with synthetic polymers rendered shiny by layers of varnish. How could this be classified as Indigenous art?

Kimberlee Weatherall in her abstract Culture, Autonomy and Djulibinyamurr defines this style of artwork as representative of Urban indigenous artists, “non members of traditional communities, and hence are not bound by customary laws”.1 Their art subtly articulates pressing concerns regarding their surroundings and expresses political consciousness rather than communal culture. Urban artists seek their identity and autonomy by melding together two very distinct culture and creating a language of signifiers and signified that speaks to both western and non-western cultures.

Hobson has herself been subject to domestic violence and was deeply affected at how common drunken violence was amongst her urban communities. She lends from abstract expressionism by attacking the canvas using a broom laden with color. It is the dramatic performance by which her work is created that pronounces its message so clear. The speed at which her work is created is also clearly defined by the pace of life currently surrounding her. Similar to pollock, choice of material is deliberately banal, synthetic in every way and varnished to produce a polished product, fit for the glossy pages of at art catalogue.

Do you think this conjunction of two cultures makes for better communication in the aboriginal art market? Or could degrade the tradition artforms used for expressing aboriginal heritage?

1. Weatherall, Kimberlee. (mar., 2001) Culture, Autonomy and Djulibinyamurr: Individual and Community in the Construction of Rights to Traditional Design. The Modern Law Review Vol. 64, No.2 pp 238—239.↩